Why do we climb mountains?

I had been brooding the answer to this question during my last expedition, attempting to summit Everest without supplemental Oxygen in 2021.

Is it simply because it’s there? Yet, It was what I saw on Everest that helped to answer my burning question.

I saw people wanting to be the best, the first, and the fastest. And if they were unable to fit into these categories, they created one of their own. This perspective clashed with my values. For me, climbing was always more about myself. I don’t have to be the first, or best, and although I enjoy pushing my limits, It's more about watching golden sunsets and cherished moments with friends, and of course being outside, immersed in my surroundings.

Then I began to wonder. Could climbing be used for something bigger than myself? Perhaps as a source of inspiration, a catalyst for change, and difficult conversations. I’d held onto an idea for a couple of years. Climbing all 4000m peaks in the Alps, solo and in one push.

The seed for this idea was planted in 2018 while climbing Arbengrat on the Obergabelhorn (4063m) with one of my clients. Together we were discussing my projects (K2, Moonflower, Cassin ridge, Cholatse, Manaslu), and my feelings toward these expeditions.

I had already climbed a handful of 4000m peaks solo. These climbs were some of my most memorable and beautiful alpine outings. Not for the difficulty, but because of the feeling of immersion in the mountains, setting my own pace, and unshackled from the responsibility of a companion. I was free to enjoy the terrain, cast my eyes across the views, and fall into a flow state as I worked my way to the summit.

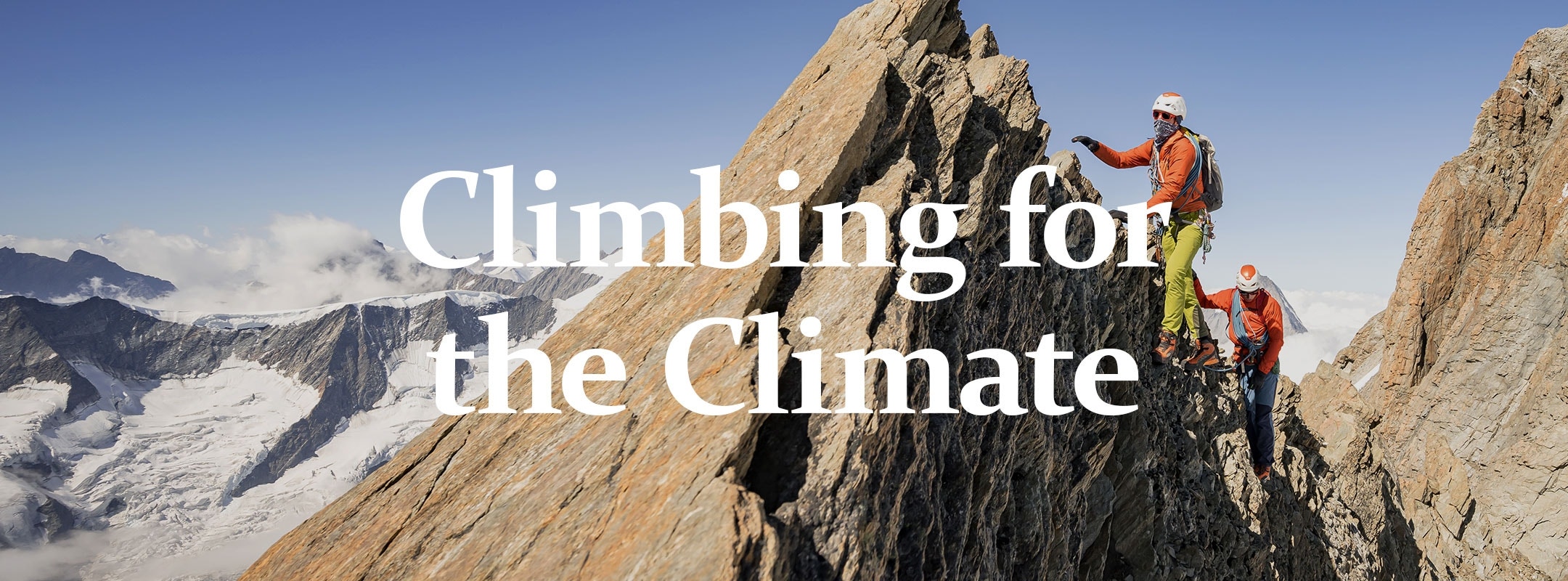

These experiences shaped me. But I wanted to use climbing for something bigger than myself. I wanted to use it as a tool to show people another way. The project needed not to be about me, but something bigger. And after the things I had seen over the last years in the Alps with climate change, it felt like the only logical issue to address.

Our glaciers are melting. Rock towers are crumbling. Seasons are out of sync, and the droughts and floods are alternating. And yet, it feels like hardly anyone is doing something about it.

I'd made my decision. I was going to climb all 4000m peaks in the Alps self-powered while documenting what was happening from my perspective. I want to demonstrate that you can tackle big adventures without a big CO2 footprint and that it’s the small things that collectively make the biggest impact.

I wanted my challenge to be an inspiration and a positive example. If only I had known then what a dangerous summer I had picked for my adventure.

Happy, enthusiastic, and full of confidence yet ignorant of what lay ahead I pushed forwards on my pedals and launched myself down the road. I was yet to know that the very issue that motivated my challenge was to be a hurdle from the very beginning. I had planned on climbing Piz Bernina, the highest peak in the Eastern Alps, at 4,048m. No climber had yet to summit Piz Bernina this season due to the condition of the glaciers and further up the mountain. When we ascended the mountain on my skis I understood why.

The glacier was dry, with crevasses everywhere, creating a cold hostile maze to navigate through as we advanced to the Marco e Rosa hut. We attempted to make for the summit but only to be repelled back to the hut with tiredness and altitude sickness. Uncowed, we slept, woke early, and advanced toward the summit. The rock ridge leading to the summit is exposed, but not difficult in ordinary conditions. Yet it was filled with soft snow, packed down on slabby rocks. The conditions were scary, and after lots of careful traversing sketchy exposed edges, we summited on the 28th of May 2022. The descent was long and endless. We arrived in the valley late into the evening with the first peak completed, but my confidence eroded.

Happy, enthusiastic, and full of confidence yet ignorant of what lay ahead I pushed forwards on my pedals and launched myself down the road. I was yet to know that the very issue that motivated my challenge was to be a hurdle from the very beginning. I had planned on climbing Piz Bernina, the highest peak in the Eastern Alps, at 4,048m. No climber had yet to summit Piz Bernina this season due to the condition of the glaciers and further up the mountain. When we ascended the mountain on my skis I understood why.

The glacier was dry, with crevasses everywhere, creating a cold hostile maze to navigate through as we advanced to the Marco e Rosa hut. We attempted to make for the summit but only to be repelled back to the hut with tiredness and altitude sickness. Uncowed, we slept, woke early, and advanced toward the summit. The rock ridge leading to the summit is exposed, but not difficult in ordinary conditions. Yet it was filled with soft snow, packed down on slabby rocks. The conditions were scary, and after lots of careful traversing sketchy exposed edges, we summited on the 28th of May 2022. The descent was long and endless. We arrived in the valley late into the evening with the first peak completed, but my confidence eroded.

I’d believed Piz Bernina to be one of the ‘easy’ peaks. Yet it seemed that the conditions on the mountain were so different to seasons past, that the difficulty had changed for the worse. And only after two long days I already needed a rest day to recover.

Had I overplayed my confidence? Was my idea absurd?

Doubt filled my mind. Yet we persevered and started 3 days of biking, covering 275km, over 3 big cols, and arrived in Saas Grund in Valais. Luckily my climbing partner was an experienced cyclist and his support during the ordeal was invaluable.

The following days were more successful. We rested upon our arrival in Valais, before walking up to the Brittania hut above Saas Fee. The following day we attempted two other 4000m peaks before having to turn back due to a severe, unforeseen storm. Nine days into the project and I had only ticked a single peak. The forecast warned of more unstable weather with difficult conditions in the mountains. My confidence was further eroded. What did I start??

Things began to change when I started climbing with my second climbing partner. In the following days (10 until 23) we managed to climb 25 4000m peaks around Zermatt. Many of them were in poor condition. Yet we pushed through because the peaks were not particularly difficult, and the determination of my climbing partner, who had also tried to climb all 4000m peaks previously. My confidence grew with each peak, and I believed that perhaps within 100 days we could climb them all. In the following days, I rested, and ticked 7 more peaks in the Bernese Oberland, making the total count 33.

But then I had to make a decision.

The summer of 22 was different because the winter of 2022 was extremely dry. This meant the glaciers, normally coated in snow were bare, and the crevasses were coming out, and only getting wider. Approaches became snow free which means more crumbly rock and accessing routes treacherous. Temperatures were rising, and the forecast was warm and sunny. I had to act.

Before I began my journey I made a list of which mountains I wanted to climb, and in which order. Thanks to the advice of a colleague, I also made a list of mountains that had to be climbed in certain conditions and mountains that were almost always possible to climb. Chamonix was always going to be the bottleneck because so many of the surrounding mountains needed special conditions. After a day of rest and looking tirelessly at the forecast and trip reports I jumped on my bike and pedaled to Chamonix to go for all the surrounding peaks.

From Day 37 through to 51 I climbed all the big 4000m peaks around Mont Blanc with my 3rd and 4th Climbing partner. Aig, Verte, Diable Ridge, Grandes Jorasses, 4000m peaks on the Brouillard and Peuterey ridge, and of course the Mont Blanc itself. Because the weather stayed stable, I could just climb one after the other, with only a few rest days. After I summited Mont Blanc, dome du Gouter, and Aig and Du Bionassey on day 51, I walked more than 25km back to Chamonix and enjoyed a well-earned night's sleep knowing I had totalled 61 peaks.

Mont Blanc was behind me and I focused on the remaining peaks. From Chamonix, I chose to bike to Grindelwald and approached the Schreckhornhut on day 55 with my climbing partner Jasper. From there we climbed climbed Schreckhorn and Lauteraarhorn, following the amazing linking traverse. The rock was beautiful, with a picture-perfect backdrop. The next block of climbing brought me from Grindelwald back to Zermatt, where we did the whole Obergabelhorn-Bishorn traverse, and the Mischabel traverse (Täschhorn to Durrihorn, in a long day). After that, I made a quick solo up the Matterhorn, before biking toward Italy.

I had climbed 75 peaks, and my body was feeling strong but I was ready for the finish. I’m not a very experienced cyclist, yet I found myself unexpectedly enjoying the biking more as the trip went on. Perhaps it was the lack of crevasses, falling rocks, or early starts that heightened my enjoyment of traveling by bike but it felt great to be rolling over the tarmac.

I pushed through the last 7 summits with Robin. We went harder than before like a marathon runner sprinting toward the finish line. I wanted to finish, but the worsening conditions were catching up behind me. Finally, I summited the last two 4000m peaks in the Ecrins on 12th August at 10.10 in the morning.

Tired, wasted, happy, and amazed that I had pulled it off.

The summer of 2022 was not a brilliant one to have a project like this, but it was a summer that sadly demonstrated perfectly what the big issue is: extremely hot and dry, in which many routes were closed due to rock and ice fall, with several major incidents in the mountains that could be directly related to climate change. During the project I biked 1300+ km, walked 600+ km, and got up more than 100.000+ vertical meters: with that, I became the first Dutch person and the fourth climber ever to pull this off! Yet this was not why I set out to complete the challenge. I wanted to activate people to make a change through small, incremental actions that add up.

I had helped to inspire 130 individuals to pledge a change within their life for the benefit of the climate. The challenge also generated a lot of attention for the bigger issue and how we can all do something small that matters. Like Albert Schweitzer said: ‘Example is not the main thing in influencing others. It is the only thing’

Listen to the full story

Listen to Roelands chat with Andy Cave on the Mountain People Podcast on Apple, Spotify or anywhere you listen to your favourite shows.

You can also learn more about Roeland on his personal website by clicking here.

Large subhead (32px text, 38px line height)

Small subhead (20px text, 28px line height)

Text paragraph

Shop The Kitlist

Words by | Roeland Van Oss

Images by | Ben Tibbets

Words & images by | Athlete Name

Author bio in italic 16/24 body style with grey text colour.

Read more about Athlete Name here