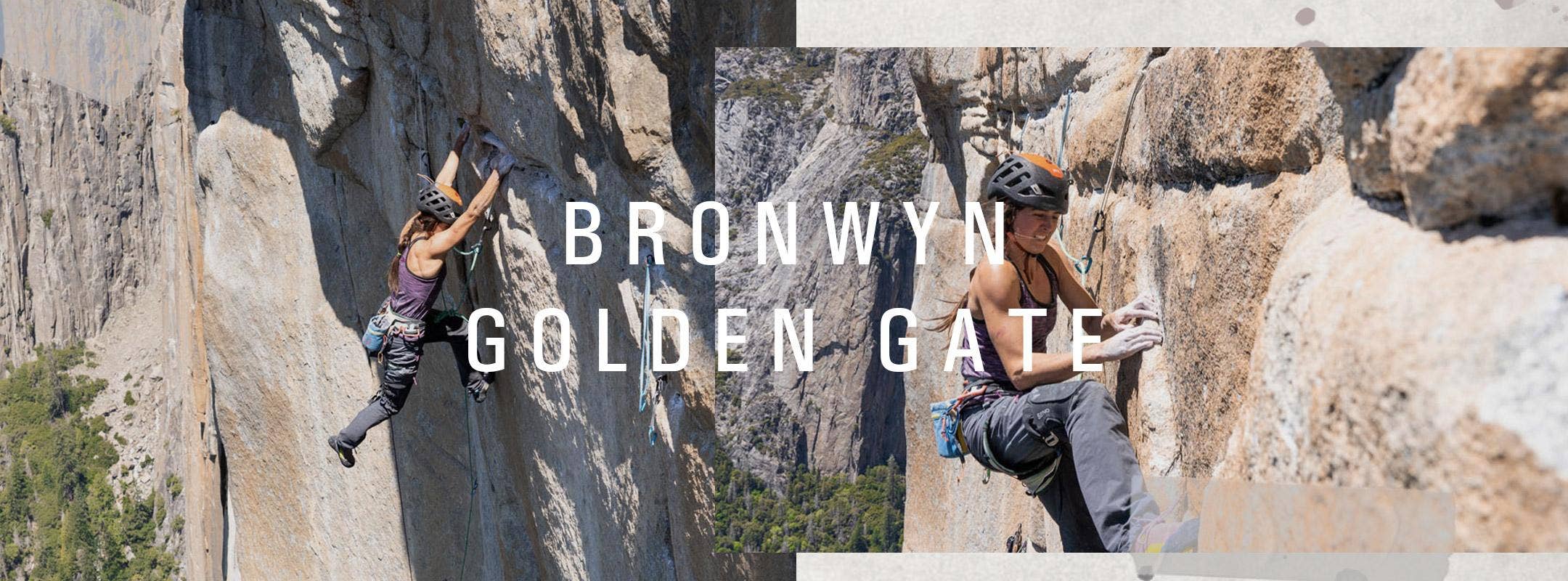

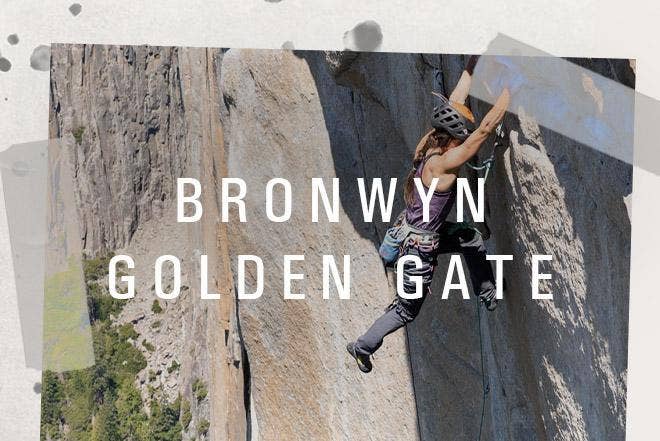

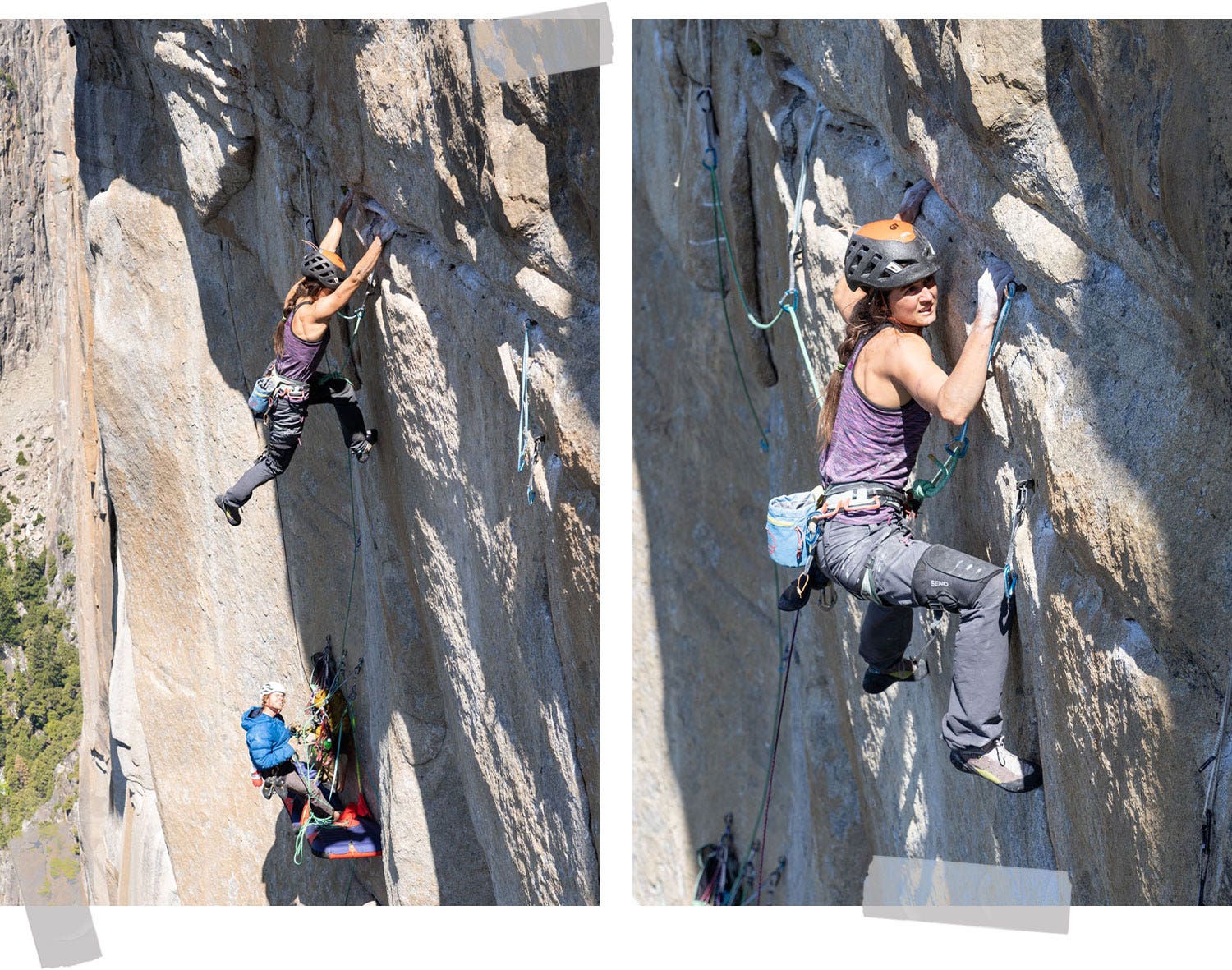

In May 2021, Canadian climber Bronwyn Hodgins became the third woman to free Golden Gate, a 34-pitch 13a (7c+) on El Capitan in Yosemite, California.

The ascent took her eight days from ground to summit, and was the culmination of six months of specific training and preparation. Established in 2000 by German brothers Thomas and Alex Huber, the route shares the first nineteen pitches with Freerider — climbed by Alex Honnold without a rope in 2017. From there, Golden Gate cuts right up a gradually steepening upper wall with four distinct cruxes: The Downclimb (pitch 19), The Move (pitch 24), The Golden Desert (pitch 28) and The A5 Traverse (pitch 29).

Large subhead (32px text, 38px line height)

Golden Gate: By Bronwyn Hodgins

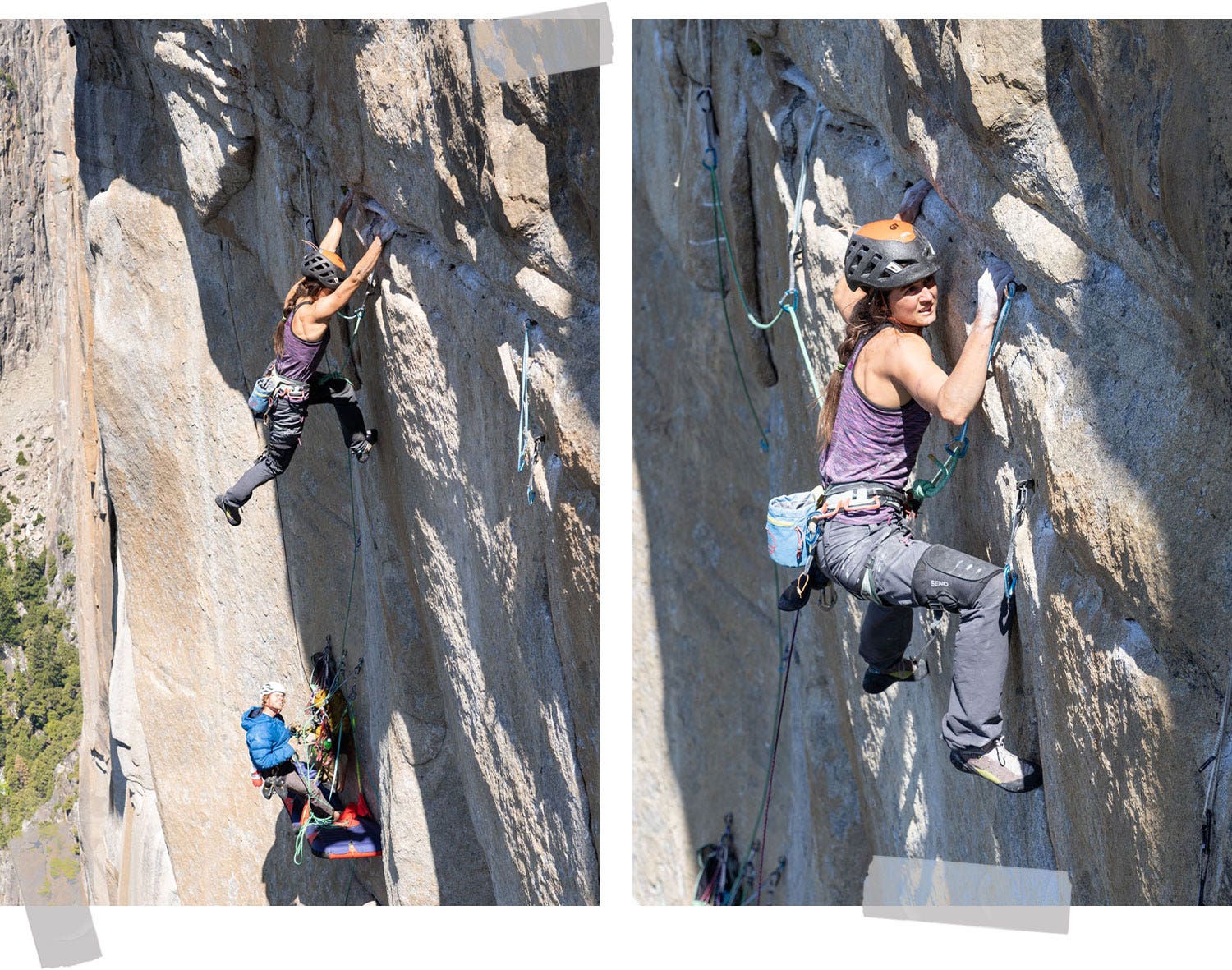

Pink light was fading on the horizon, marking the end of our fifth day on the wall. I pulled onto the rock and danced delicately up the rippled face to the jug below The Move. Shaking out my arms one at a time, I closed my eyes and visualized my sequence.

The Move. It’s all in the name. One heinously hard, fiercely shoulder-y move. One stopper move just below the chains of pitch 24, on a 34-pitch free route on El Capitan. The Move is said to be harder if you’re short. So hard that Hazel Findley, the first woman to send Golden Gate in 2011, wrote an entire blog post about it. So hard that Emily Harrington, who nabbed the second and only other female ascent, broke down in tears on it in 2015.

It’s funny to think that a vertical kilometre of climbing could come down to a single move.

I took a deep breathe. I was putting so much pressure on myself, but I had to let go of all that baggage. I was going to fight as hard as I could — that was all I could do.

I locked off the double gastons and caved my upper body out from the wall, making space to bring my left foot to my belly button. Using tension in my core and shoulders to roll my weight onto that insanely high foot, I ninja kicked my other foot onto a microscopic jib out right. Pressing hard on the jib, I stabbed my right middle finger desperately for the mono, letting out a little power squeal with the effort…

I was in the mono. I couldn’t believe it!

Focus. Keep it together. Breathe. I eyed up the series of pockets that traversed to my left, and then started across them, smearing my feet. My foot slipped and I came sailing down onto the rope. Nooooooo! I couldn’t believe I’d fallen after The Move! But even more so, I couldn’t believe that I HADN’T fallen during it! My astonishment outweighed my disappointment.

An hour later night had fallen. I put on my headlamp and set off again, each hand and foot finding its place, my focus never wavering until I was romping up the final line of jugs to the anchor.

The idea of trying Golden Gate crept into my mind at the end of summer 2020. Two years had passed since I’d been to Yosemite and climbed Freerider on El Capitan, and I felt my motivation building for another big goal. However, Golden Gate felt like a huge step up. I knew the four crux pitches would be really hard for me, especially The Downclimb and The Move, as both are fiercely bouldery. I’m naturally an endurance athlete and my body has always struggled with pure maximal power. Would I be able to stay fresh enough to perform near to my physical limit on these extremely bouldery moves on the top half of the wall? Honestly, that seemed unlikely.

But a part of me was curious.

I made a winter training plan, which involved moving to St George, Utah, to focus on sport climbing. My preparation would be twofold: physical and mental. Physically, I needed to be in the best climbing shape of my life. The mental training was more nuanced. On Golden Gate I wouldn’t have excess time nor energy to flail on the hardest pitches. I’d have to send each one in as few goes as possible, separated by strategic recovery. In St. George therefore, I dedicated myself to honing the art of efficient redpointing — executing a near flawless performance in just a few attempts — sending close to my limit, fast!

In hindsight, I believe this mental training was the biggest factor that led to my success. The months of practice performing under a self-imposed pressure to “send quick” all winter gave me the fine-tuned visualization skills and, more importantly, the confidence that I could perform well when it mattered. During my 8-day ascent, there was immense pressure placed on each attempt at a crux pitch, and I managed to maintain unwavering focus and execute every time.

By April, my beta retention and execution was at an all-time high and I’d become fit and strong in the process. But would it be enough? I still had a lot of doubt. Maybe this goal was just too hard for me. Should I have been training more shoulder strength and bouldering? What if I simply can’t do The Move? The confidence struggle was relentless and exhausting.

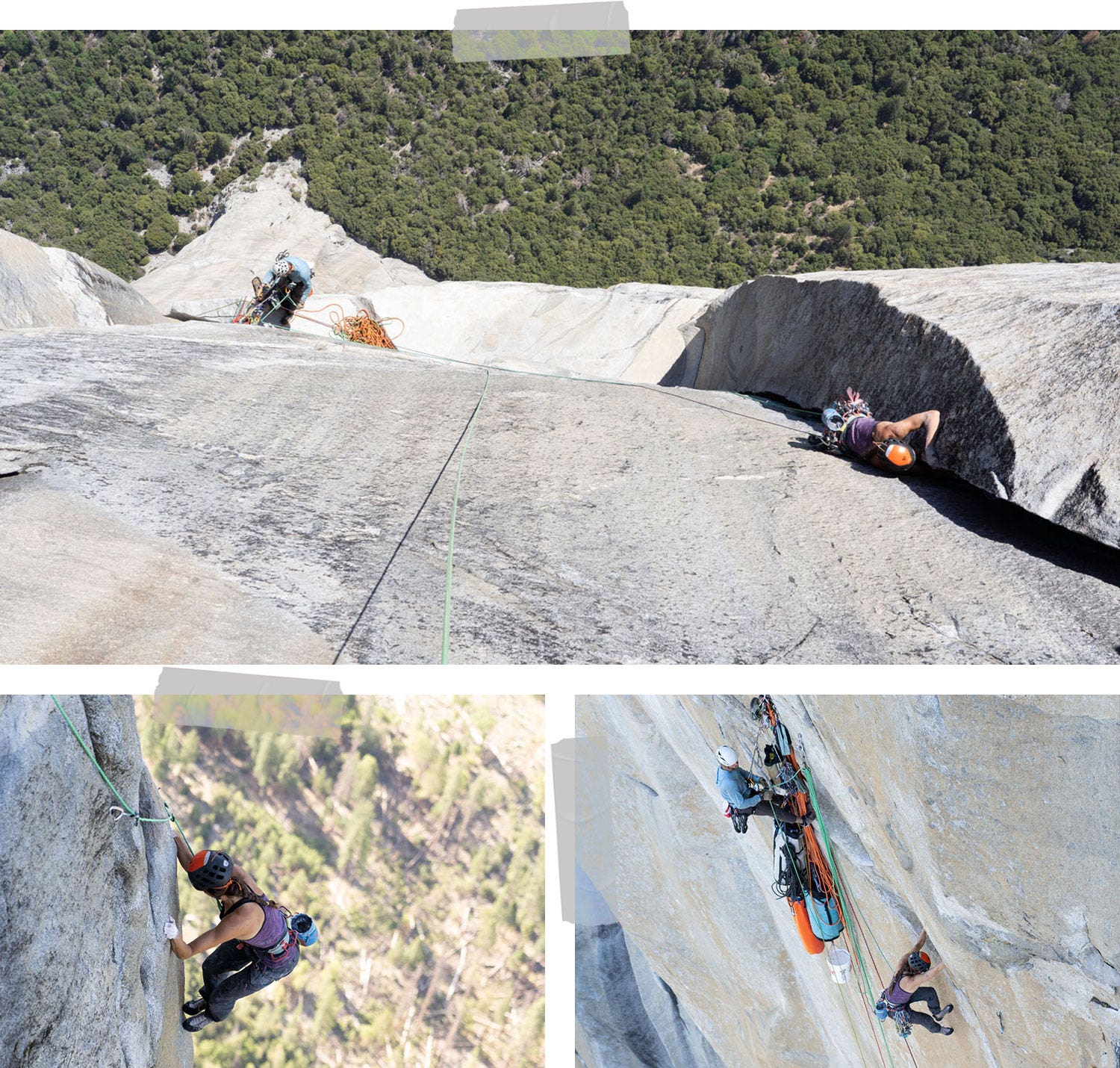

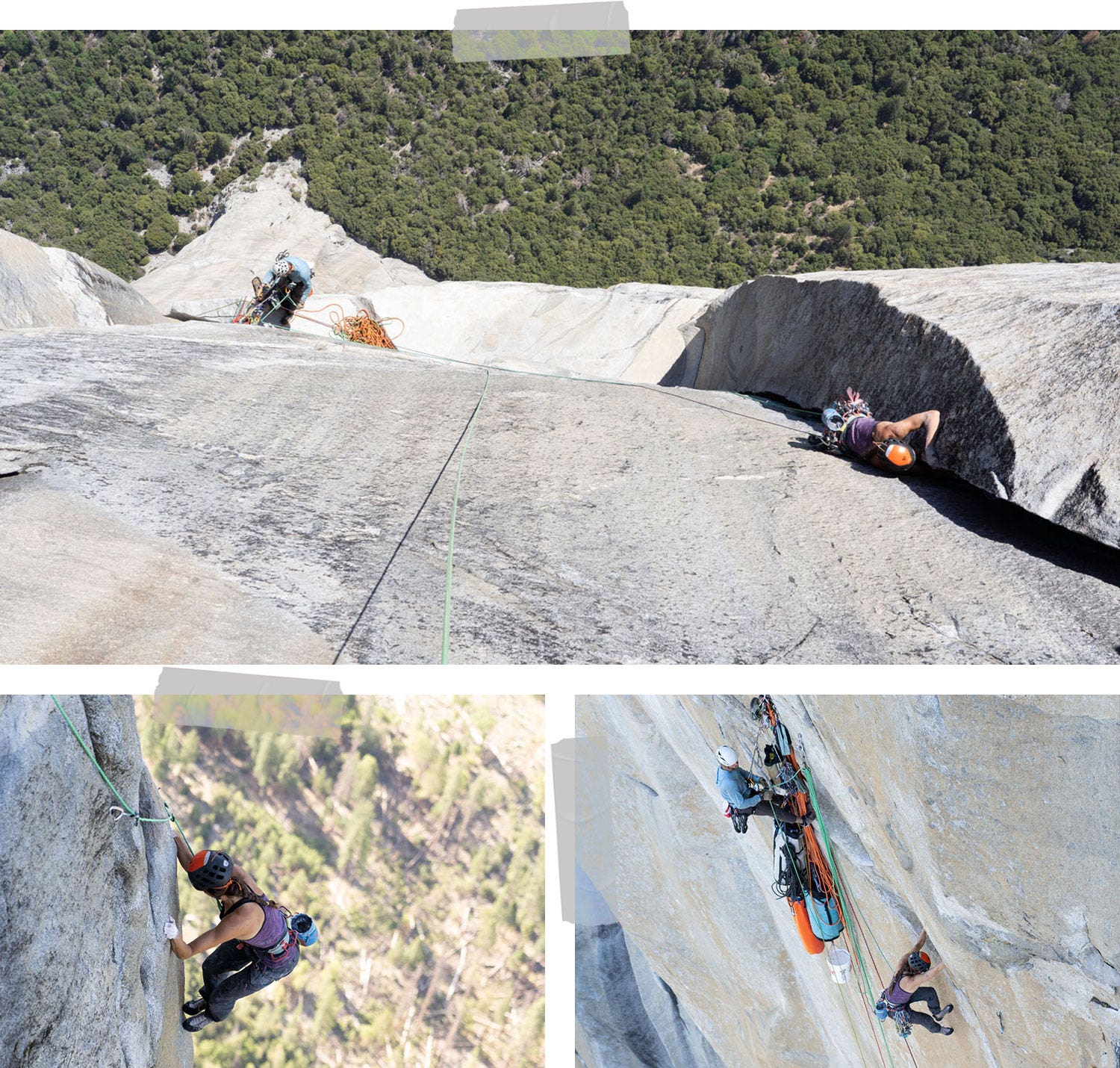

I arrived in Yosemite and was instantly overwhelmed with awe and wonderment standing under El Capitan. I was antsy to try Golden Gate’s crux pitches. My friend Taylor Woodruff helped me lug 300m of static rope to the summit — getting to specific pitches in the middle of El Cap is no easy task! We rapped in to try the The Move pitch for two days. I didn’t do The Move. I didn’t even do the move before The Move! Did I really think I was about to free climb Golden Gate!? Was I driven and dedicated? Or simply delusional?

We hiked back down into the valley, but my mind stayed up on the wall. I needed to find a right foot. That would get my body into the correct position to cross to the mono pocket (yes, a mono on El Cap!). I messaged Emily Harrington asking for short person beta. She told me about a tiny foot jib on the right wall: “way higher than you think and way smaller than you want, but it’s there!”

A few days later I was back at The Move, swinging about with, another friend, Alix Morris. Sure enough, I scanned the smooth right wall and found a tiny jib. It seemed impossibly high. I pulled into the gastons, Ninja kicked my right foot high onto the jib and stabbed my right middle finger into the mono. I froze. Then looked up at Alix, her eyes as wide as mine: “Yeah Bronwyn Almighty!” she cheered. The Move had been on my mind all winter. This pitch was the culprit of most of my doubts and insecurities about this ambitious goal. I climbed the final few metres to join Alix at the anchor. I can do The Move! This goal is ON!

Back down in the valley, I stared intently at the calendar on my iPhone. The days were ticking by. As a Canadian I’m allowed 6 months in the USA, which would expire May 19th and it was already May 1st. I hadn’t managed as much practice on the crux pitches as I’d hoped for and I didn't feel ready. Dates weren’t aligning with my original partner and now I was scrambling to find another. I’d been planning this climb for six months: how did I end up two days before I wanted to set off without a partner? Should I just give up for this season and come back in the fall? I very nearly packed up and left. The idea of this whole thing coming together suddenly felt so unlikely. Maybe it was easier to run away…

I met Danford Jooste for the first time in Degnan’s Deli. He sat smiling and sipping his coffee; he seemed slightly bemused by my manic dedication to my goal. His mop of dirty blonde hair stood on end, the classic dirtbag haven’t-showered-in-a-while look.

Me: “Hey, so… I hear you might be keen to head up on Golden Gate with me?”

Danford: “Yeah, I just found out about it this morning, seems like a neat opportunity. I’m in.”

Me: “Wow! Really? And you’re cool to start like… day after tomorrow!??”

He was all game and smiles. I felt incredibly lucky. Despite all the careful planning and preparation, being successful at big wall free climbing seems to be just as much about improvisation and chance.

I called my husband Jacob Cook on the phone in a whirl of emotion. Jacob has always been a huge inspiration in my climbing. He consistently sets outrageous goals and scrapes through with success more often than not. His support and belief in me too has always amazed me, dared me to dream bigger and open my mind to what might be possible.

I made the decision to give it go.

Golden Gate Kitlist

Quote style, bold, italic, 20px over 28px

Words by | Bronwyn Hodgins

Bronwyn is a professional rock climber and guide, based out of Squamish, Canada. Originally from rural Ontario, she grew up canoeing, hiking and skiing with her family. She started climbing at university and immediately fell in love with the sport.

Read more about Bronwyn here